The presentation of the Union Budget 2022-23 is just around the corner and like every year, there are many expectations from it so far as children are concerned. While every year around the time of presentation of budgets a lot gets discussed and debated about the budget numbers that are earmarked and spent for children, less light is shed on how the process of child budgeting is actually carried out in the country. The latter is an equally important factor in achieving better outcomes for children in the long run.

Budgeting for children by the Union Government had started as early as 2008 with the publication of the first-ever Child Budget Statement. Subsequently, several states have also initiated the practice. However, even after a decade, child budgeting is still a long way from translating into desired outcomes for almost two-fifths of our population.

What do the existing data say about the state of children in India?

The recent NFHS 5 survey has revealed a mixed picture on child health and nutrition. On one hand there are definite positives like reduction in child mortality rates, improvements in the levels of nutrition indicators like stunting and wasting etc. On the other hand incidents of anemia among children have gone up from 58.6% in NFHS 4 to an alarming level of 67.1% in this round, leading experts to point out that more efforts are needed for meeting the 2030 SDG targets. The consecutive ASER surveys have pointed out that there has been no improvement in the proportion of children currently not enrolled in school between 2020 and 2021 and there exists a lot of variability among the states in this regard.

Where lies the gap?

A sound public finance management (PFM) roadmap for children is an important entry point for addressing many of the concerns highlighted above. Unfortunately, budgeting for children by the Union Government has remained limited to being a mere annual accounting exercise culminating in the publication of the Child Budget Statement (CBS) by simply collating relevant budget heads across departments. This alone does little to address the core objective of initiating such a strategy in the first place, which was to ensure that the government’s budgeting process, in its various stages, remain responsive to the special needs of children. In other words, child budgeting needs to be integrated throughout the planning, budgeting, implementation and monitoring by the governments.

State Governments, being mainly responsible for implementing many of the critical schemes for children play an important role in taking this exercise forward. But even for them, the latter has mostly been perceived as an accounting responsibility rather than as a tool to plan and execute interventions for children more effectively.

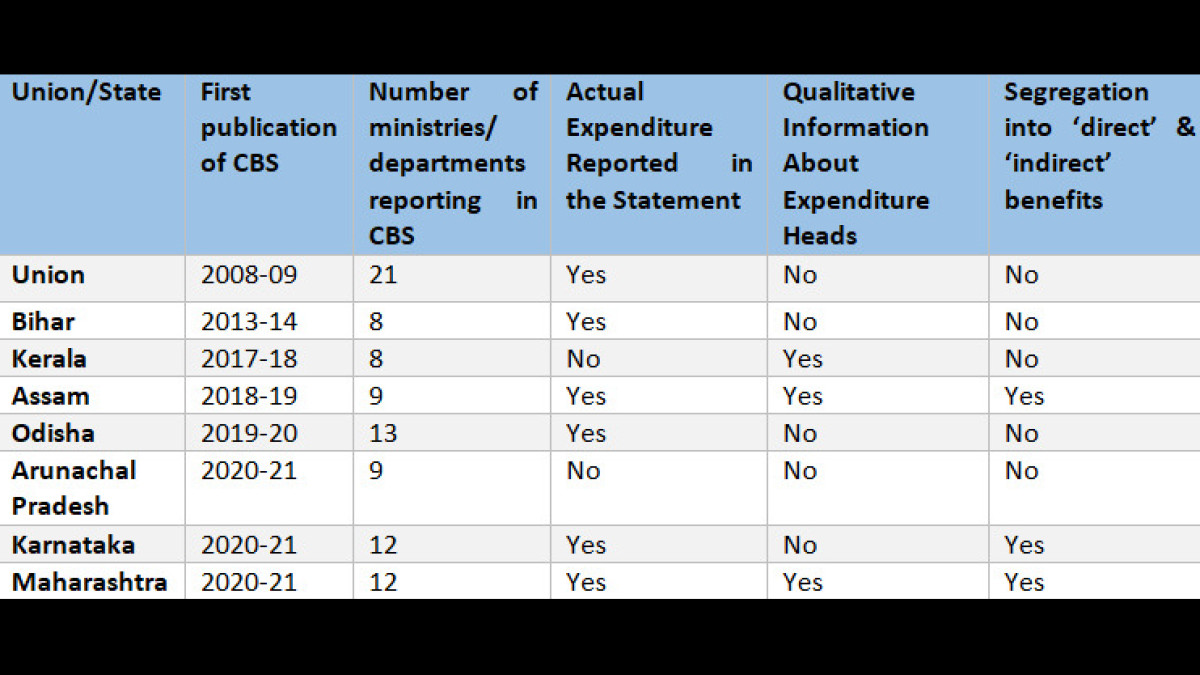

Moreover, there is a lack of standardisation of norms among government entities for reporting in their respective CBS. While some states include both ‘direct’ and ‘composite’ benefits[1] for children, others report actual audited expenditure on the schemes and programmes in addition to the outlays. The inconsistent reporting across different states precludes any meaningful comparison of the reported numbers and renders the CBS less effective as an accountability instrument. The matrix below provides a snapshot of how reporting is done in the CBS by the Union and State Governments.

Source: Compiled by CBGA from the CBS of Union and State Governments, 2021-22

What can be done better?

With the Union and respective State Budgets scheduled to be presented shortly, it is an opportune time to revamp child budgeting as a robust PFM strategy. The following concrete steps can be considered.

- Orientation of the government officials working on child-related interventions through capacity building programmes is important, not only for reporting in the CBS but also for enabling them to redesign schemes better and monitor the progress on a regular basis. While some states like Assam, Karnataka, etc. have initiated efforts towards this, the Union Government can consolidate all such initiatives into a training and orientation plan at the national level.

- An outcome orientation of the budget for children is essential for translating the outlays into better outcomes. Thus, the exercises of Child Budgeting and Outcome Budgeting need to be carried out by the government not in silos but in coherence with one another.

- There is an urgent need to standardise the reporting structure in the CBS and the Union Government can develop a detailed framework for it in consultation with states and domain experts to make CBS an effective instrument of accountability as well. This can encourage more states to extend efforts in this direction as well.

- Regular monitoring and audits of relevant child related schemes must be taken up by the respective ministries. This would not only enable systematic collection of reliable data on child beneficiaries and other relevant indicators but the insights from this process can be incorporated into next year’s budget planning and scheme designing for children, thus making it an integrated approach.

- To drive all of the above interventions, a nodal committee, or a budget cell, chaired by senior bureaucrats and with members from the administrative and finance departments must be activated. The Union Government directive to reposition the ‘Gender Budget Cell’ as ‘Gender and Child Budget Cell’ is a welcome move in this regard, but it must be backed by a strong political will to make this body well-functioning within the government.

Child Budgeting alone might not be a magic pill to solve all issues of children, but rethinking the process and strengthening the systems and institutions involved can certainly go a long way in realising their rights and ensuring their holistic development.

[1] ‘direct’ benefits include schemes which are exclusively targeted for children like Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, Mid Day Meal etc. Examples of ‘composite’ benefits include schemes like Post Matric Scholarships, National Health Mission etc. for which children are one of the beneficiary groups.

25 January, 2022

25 January, 2022