The modern taxation system is based on the principles of two equities – Horizontal Equity and Vertical Equity. Horizontal equity means people with same income/wealth should pay same tax; while vertical equity means that people with higher income/wealth should pay more tax. Broadly, these principles combined are also known as ‘Ability to Pay’ principle of taxation. A tax system which follows these principles is termed as a progressive one, while the system which doesn’t follow these principles is termed as a regressive system.

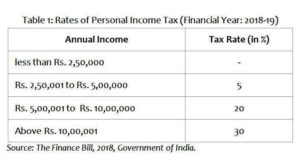

The most common manifestation of ‘ability to pay’ principle is differential tax rates levied on the income. Generally, income tax is levied only on the incomes above a certain threshold, which essentially is acceptance of the idea that incomes below a certain level are too low to be taxed. And even for the income that is taxed, there is generally an increase in the tax rate as the income level goes up. This is certainly the case in India as can be seen from table 1 –

Because of these differing rates, as the income goes up, the tax paid also goes up – in the absolute amount as well as the proportion of income. Graph 1 represents this trend of income and tax paid as the percentage of income.

As depicted in the graph, the effective tax rate[i], which is the amount of tax paid as percent of income, rises with the level of income. However, the noticeable thing is that rate of increase in effective tax rate is much sharper at the lower levels of incomes and becomes flat at the higher levels of income. For example – when the income of a tax payer increases from Rs. 10 lakhs annually to Rs. 20 lakhs, the effective tax rate increases from 11 percent to 20.5 percent; but when the income of a tax payer increases from Rs. 1 crore to Rs. 1.5 crore, the effective rate goes up only marginally – from 28.1 percent to 28.8 percent.

There are primarily two reasons for this lopsided increase in the tax payable-

-A large increase in tax rate from 5 percent to 20 percent between the two lowest slabs

-Peak rate a very low level of income – the starting income to levy 30% tax rate is Rs. 10 lakh, which is merely twice of the income in the lowest slab, i.e. Rs. 5 lakh

Both of these factors combined produce an outcome, which technically can be classified as a progressive one, but it certainly is not a desirable one. A fair tax system should be the one which sees a more gradual increase at the lower levels of income and much sharper increase at the higher level.

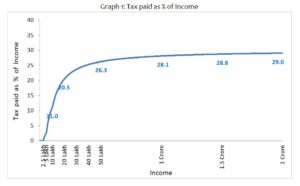

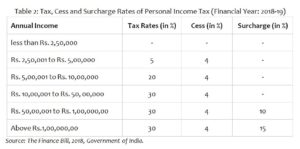

Indian government has tried to compensate partially for this shortcoming through an indirect method of cess and surcharges, which are additional taxes levied on the amount of tax payable. The rates of cesses and surcharges that are levied on personal income tax in India are given in table 2.

The inclusion of cess and surcharge changes the tax payable calculation as follows – after the calculation of tax payable as per the income tax slab, surcharge is calculated by multiplying the corresponding surcharge rate with the tax payable. The amount thus calculated is then multiplied by the cess rate to arrive at the final amount. Simply the formula is –

Total Tax Payable = (Tax Payable as per the income tax slab) × (1 + surcharge rate/100) × (1 + cess rate/100)

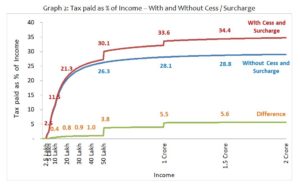

Thus, cess and surcharge result in higher tax payable compared to the earlier calculation. The relationship between the income and the tax payable inclusive of cess and surcharge is presented in graph 2[ii].

The education and health cess make the tax system little more progressive compared to earlier, as can be seen for the incomes below Rs. 50 lakhs. However, the surcharges have larger impact. For the income group Rs. 50 lakhs to Rs. 1 crore – there is an average increase of around 4 percent; while for the income above Rs. 1 crore, the effective tax rate increases by little over 5 percent. Thus, overall, cess and surcharges do make Indian income tax system little more progressive than earlier.

While increased progressivity and additional revenue for the Union Government are the beneficial aspects, there are also some problem areas in case of cesses and surcharges because of the two following reasons –

-The amount of Cesses and Surcharges collected don’t form part of the divisible pool of resources which has to be shared with the States, hence are against the principles of fiscal federalism, and

-They add an extra layer of complexity for both the tax payers and the tax administrators

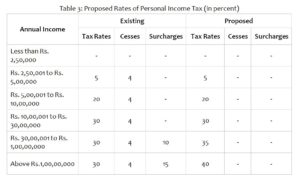

The easiest way to remove these undesirable aspects of cesses and surcharges, without the loss of progressivity or tax revenue, would simply be to eliminate cesses and surcharges and introduce new tax slabs and rates corresponding to the effective rates. One such new structure of slabs and rates is presented in the table 3.

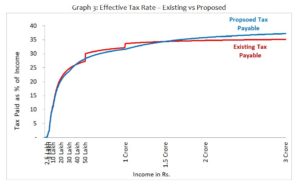

The effect of new proposed tax structure on tax payable is depicted in the graph 3.

From the graph, it is clear that except for those with income above Rs. 1.5 crore, new rates will keep the tax payable for almost all tax payers at the earlier level; hence the revenue collected by the government should also remain almost same. Thus, apart from removing the undesirable aspects of the cesses and surcharges, the proposed structure will also help in increasing, only marginally though, the progressivity of the personal income tax system in India.

N.B. – The proposed rates were arrived at only considering the removal of cesses and surcharges. There are other reasons why the current personal income tax rates should be changed, most importantly to tackle the growing income and wealth inequality, though these considerations were outside the scope of this article.

[i] It should be noted that the graphs here are based only on the calculation of tax rates. While calculating tax payable, there are some other considerations as well, such as exemptions or other special considerations, but since they are likely to be tax payer specific and not necessarily universal, they have not been taken into consideration. In that sense, the above graph represents a very close approximation but not the exact amount of tax paid.

[ii] While calculating surcharge, one additional provision known as ‘Marginal Relief’ is applied to make sure that additional tax payable doesn’t exceed the additional income. Because of this provision, the increase in tax payable at the two thresholds (Rs. 50 lakh and Rs. 1 crore) would be slightly more gradual than depicted in the graph, but for our purpose they can be taken as negligible.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author, and don’t necessarily reflect the position of CBGA. You can reach Suraj Jaiswal at

su***@cb*******.org

.

8 May 2019

8 May 2019

I found your article very informative and I totally love how the concepts are explained in this blog post. Thanks for sharing your insights. It helps a lot.