COVID-19 has exposed and amplified the class and caste-based inequality and injustice that exists in our country. Efforts by the Union and State governments to curb the spread of COVID-19, by shutting down the economy, has adversely impacted the poorest sections of the population who are largely involved with the informal sector; paradoxically, with the resumption of economic activity, these people will again be severely affected. While the former is an outcome of the economic crisis, the latter has much to do with the poor public health system in India. Thus, the twin crises will have a major impact on the lives and livelihood options of the poor citizenry.

The number of confirmed cases of COVID-19, at the moment, have been about 10,000 on an average, on a daily basis. It is the case after the nationwide lockdown was lifted. Since more than 80% of cases are asymptomatic, and only 5 per cent of infected cases are severe and require hospitalisation, one can assume that around 500 new beds are required, every day, to admit COVID patients – let alone for other health issues for which hospitalisation is required. For the last two months, other health issues have been neglected completely, as the government issued a circular asking for postponement of other treatments. This is not sustainable in the long run though, as public hospitals are going to experience an uncontrollable upsurge in demand for in-patient care in no time.

DILAPIDATED CONDITION OF THE PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM

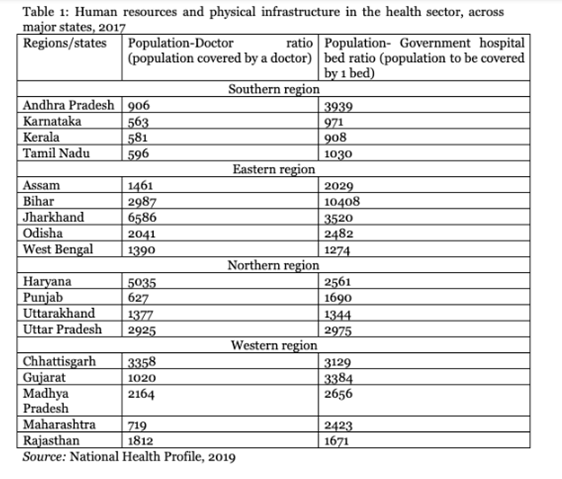

The public health system is in a dilapidated condition and public expenditure on health has been very poor, across states. Table 1 shows the neglect of the Indian state in creating human resources and physical infrastructure in health care. The table clearly shows that the three southern states of Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, have outperformed the rest in creating infrastructure—human and physical—for health care. However, same cannot be claimed in terms of bed – population ratios for those states.

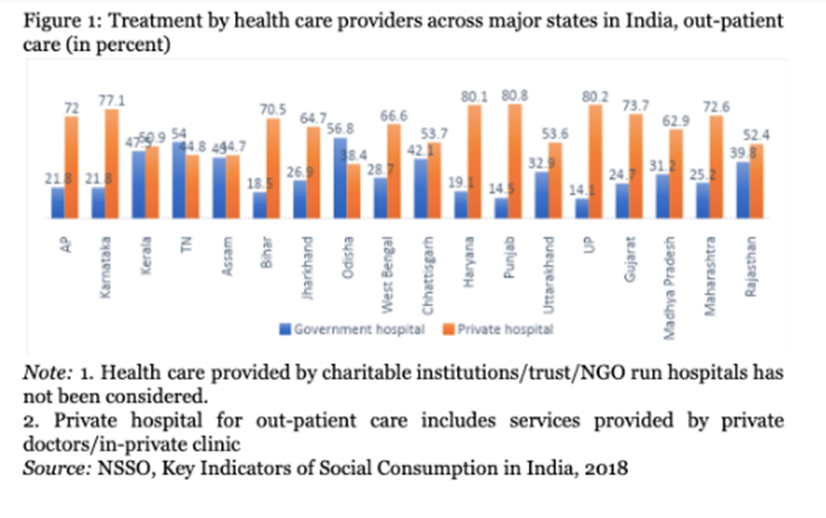

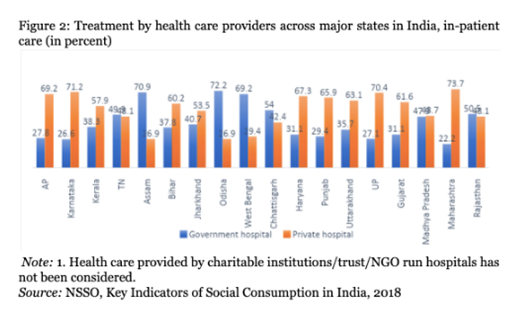

The limited reach of the state in providing health care has manifested itself in the dominance of the private sector. Rates of both in-patient and out-patient care at private health facilities are higher than those of public health facilities, in most of the major states (Figures 1 and 2). Due to unavailability of certain services, poor quality of services and long waiting times, which can be indicative of a shortfall of health professionals, people choose to go to private providers and are left with no choice but to incur higher expenses. More recent evidences regarding treatment of COVID-19 patients suggest that the scenario has remained unchanged.

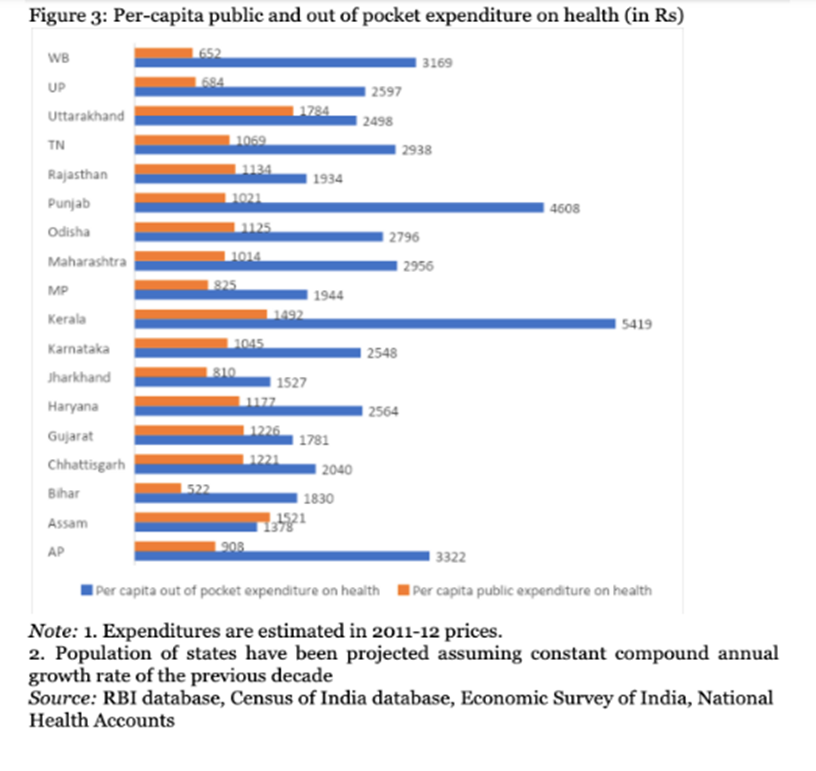

Per capita expenditures incurred by the state governments on health care, for most of the major states, has been lower than the national average of Rs 1,739. This implies that while India has been noted for an inadequate resource allocation for health care, performances of the state governments has been below par, with Kerala and Uttarakhand being exceptions. Typically, the worst performing states in terms of public intervention in health care, were also noted for higher out of pocket expenditure (Figure 3).

POOR BEAR THE ECONOMIC BURDEN DISPROPORTIONATELY

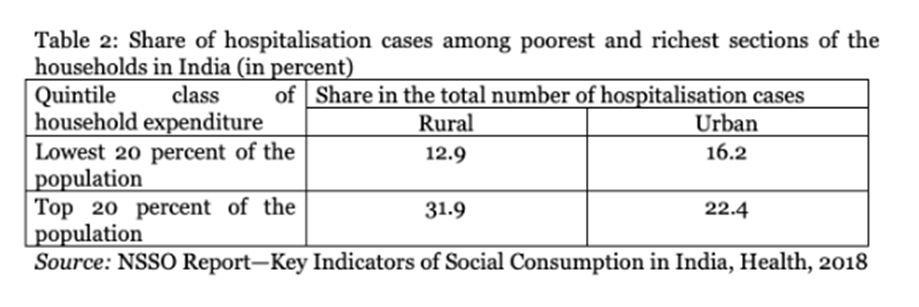

Due to high out-of-pocket expenditure, the poorest in India cannot afford to avail health care services, which is reflected in the lower hospitalisation rate among these sections, as compared to their richer counterparts. This implies that with rapid commodification of health care, in which the role of the public sector has been substantially reduced, the poorest in India did not get adequate access to health care (Table 2).

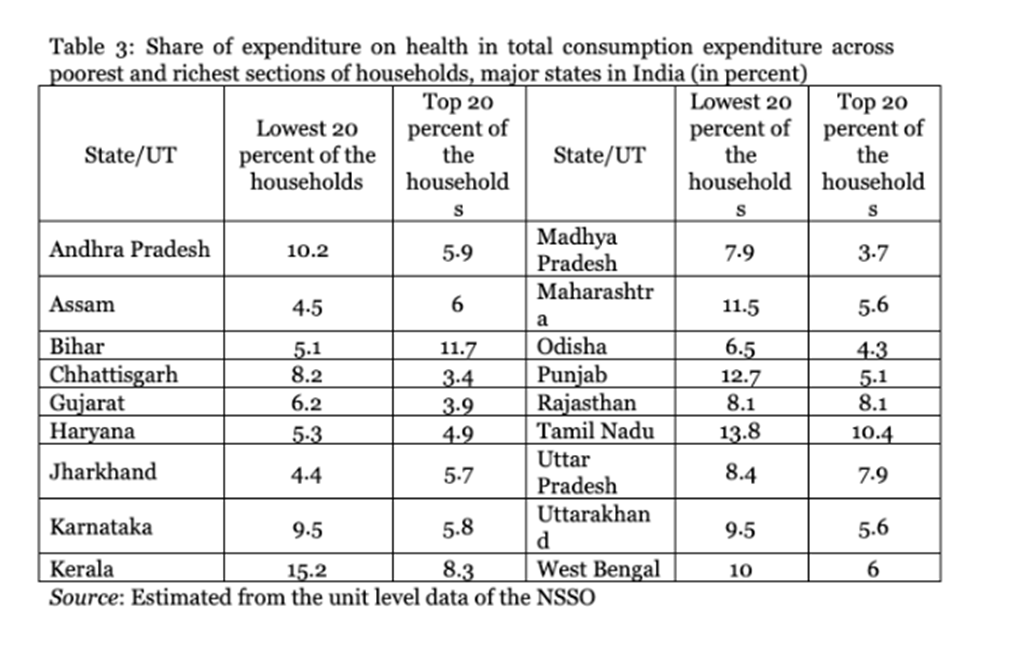

Nonetheless, a small section among the poorest, that avails in-patient care, ends up sharing a higher burden than their richer counterparts. In other words, the limited reach of the public health care system has led to the economic impoverishment of the poorest sections of the population in India. The burden of expenditure on health care, estimated as a share of the total consumption expenditure, has been higher in 15 (out of 18) major states in India for the poorest sections of households as compared to their richer counterparts (Table 3).

Among the major states, shares of the poorest were lesser than those of the richest households in Bihar, Jharkhand and Assam. This might seem to be a positive feature, since it shows a lower burden on the poorest sections of the population. However, these states were also noted for having the lowest hospitalisation rates among the major states in India. Thus, the lesser burden of expenditure on health care of the poor, as compared to richer households in these states, may not reflect desirable outcomes for the poorest sections of the population, since many among them may not want to get admitted to hospitals to avoid expenses. According to the NSSO survey (2018), hospitalisation rates in these states were 1.2 (Bihar), 1.4 (Jharkhand) and 1 (Assam), much lower than the national average (2.9).

CONCLUSIONS

It is now amply clear that the poorest sections in India have been hit hard by the pandemic. Many among them have lost jobs due to the economic crisis; now, when the economy has re-opened, a large number among them is staring at the possibility of losing lives due to the health crisis. A robust public health care system could have provided relief to the poorest, by reducing hardships associated with an impending health crisis. However, the study shows that the reach of the government in health care, across states, is limited, which has made these sections dependent on the private sector, that has led to economic impoverishment.

India, perhaps now more than ever, badly needs a strong health care system under the government, to save itself from a humanitarian disaster. To that end, the allocation of a greater quantity of resources by the state governments, which are primarily responsible for health care, is crucial. With the closing down of economic activities in the first quarter of financial year 2020-21, against a backdrop of the slowing down of the growth rate, the resource mobilisation of state governments was adversely affected. In this context, it is important to initiate tax reforms to grant greater autonomy to state governments in mobilising resources, to increase devolution of resources by the Union Government to the states, thus enabling state governments to increase development expenditure by relaxing orthodox fiscal guidelines.

15 June 2020

15 June 2020