Budget 2020 does not address the financial and resource shortages affecting nutrition interventions in India, an analysis of budget data shows. Public provisioning for nutrition is important given the persistently high levels of malnutrition in India.

Important nutrition schemes have got incremental increases, we found. Given this prolonged underfunding of the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD), these allocations may not reflect its actual requirements, data show. Additionally, the allocations are not enough to improve compensations for frontline workers who deliver critical nutrition initiatives.

The latest budget has allocated Rs 27,057 crore ($3.8 billion) to the five major nutrition-related schemes of the restructured Umbrella Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) of the MWCD. These include the Anganwadi Services Scheme (formerly core ICDS), POSHAN Abhiyaan (formerly National Nutrition Mission), Rajiv Gandhi National Creche Scheme, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PM’s scheme for mothers) and Scheme for Adolescent Girls. These schemes ensure direct nutrition interventions among three population groups: children between 0-6 years of age, adolescent girls, and pregnant and lactating women.

The allocation this year marks an increase of 3.7% from the previous year’s budget estimates or BE (the amount the government allocates for the approaching fiscal year). This rise is inadequate given past trends in funding and the human resource requirements for service delivery, as we explain later.

Malnutrition is commonly understood to be a multifaceted problem, rooted in a combination of factors across diet, health and care, linked in turn to social, economic and political factors. So related areas must also receive enough funds, such as food security, access to health services, sanitation and employment.

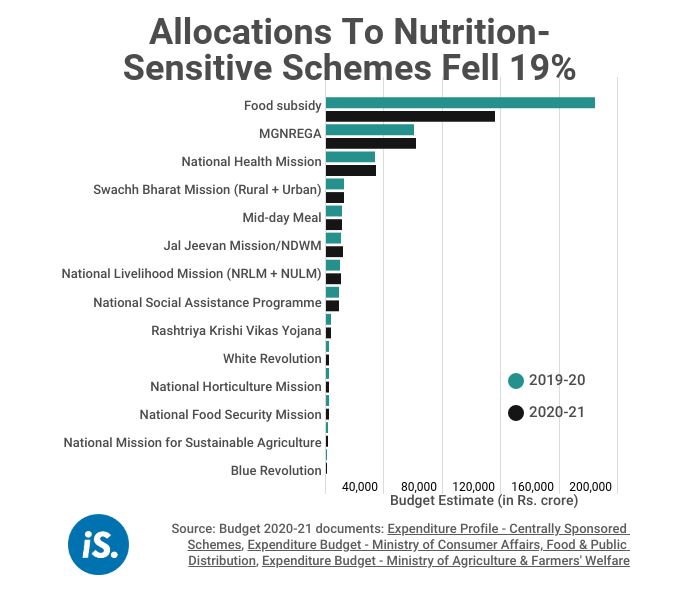

In keeping with this, a total of Rs 2,76,885 crore ($38.8 billion) has been earmarked in this budget for a basket of schemes that can be categorised as ‘nutrition-sensitive’ such as the Mid-Day Meal Scheme, National Health Mission, Food Subsidy Scheme, Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, National Rural Drinking Water Mission, and others. This marks a 19% decline from the previous year’s budget estimates (BE).

The critical Food Subsidy Scheme sanctioned under the National Food Security Act distributes highly subsidised foodgrains to 67% of India’s population (75% in rural areas and 50% in urban areas). The allocation to this scheme has been cut by Rs 68,650 crore ($9.6 billion) or 37%, compared to the 2019-20 budget estimates.

Stronger policies and system-wide capacity-building is critical in ensuring that these schemes reach their targetted recipients, several studies have suggested. This means that all nutrition-centric programmes across sectors must be adequately funded.

Underfunding leads to underutilisation of resources

Anganwadi Services, the largest nutrition scheme of the government, comprises key interventions such as the supplementary nutrition programme for children between the ages of six months and six years, severely malnourished children, and pregnant and lactating women; preschool education; and health and nutrition education. It also covers health checks, vaccination and referral services under the National Health Mission, as these have a bearing on malnutrition. This includes specific campaigns such as Anaemia Mukt Bharat (anaemia-free India), iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation, and vitamin-A supplementation.

The frontline workers who implement the two schemes are anganwadi workers (AWW) and anganwadi helpers under the ICDS, and accredited social health activists (ASHA) under NHM.

The Centre’s contribution to the monthly honorarium paid to these workers, revised in October 2018, is as follows: Rs 4,500 per month for AWWs and Rs 2,250 for AWHs, along with a performance-linked incentive of Rs 250 per month from October 2018. The ASHAs get further incentives for completing specific tasks--Rs 400 for ensuring a hospital delivery and Rs 1,200 for getting a child immunised. These workers have been demanding employee status, and an honorarium on par with minimum wages, which is Rs 18,000 for a skilled worker.

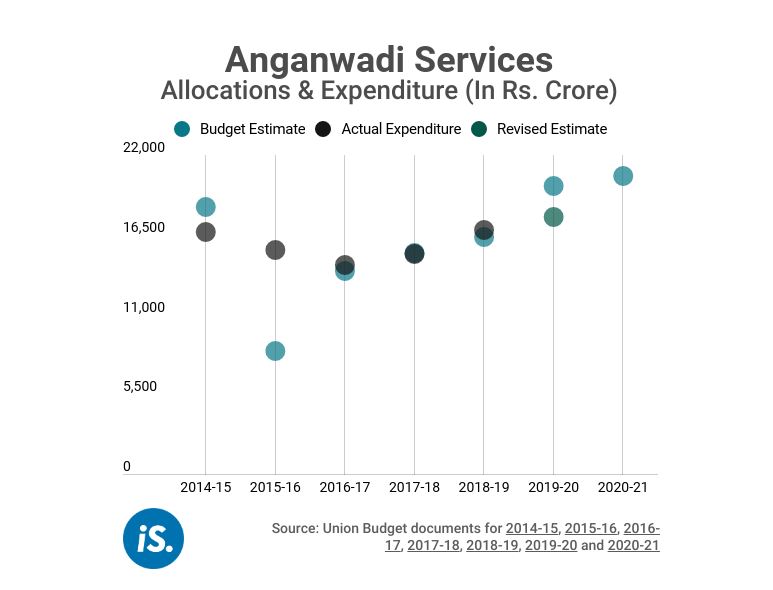

The Rs 20,532 crore ($2.9 billion) allocation for Anganwadi Services in this year’s budget--a 3.5% increase over the 2019-20 budget estimates--is not enough to offer higher compensation to AWWs across the country, particularly in light of the currently high inflation.

From 2015-16 to 2018-19, the actual expenditure on anganwadi services closely matched or exceeded the amount allocated at the beginning of the year. A Parliamentary Standing Committee on Human Resources Department observed in March 2018 that there were gaps between the MWCD’s demands and the amount eventually allocated to it.

In 2018-19, the total allocation made to the ministry was 20% less than the amount it demanded, data from the standing committee’s report show. For Anganwadi Services, the ministry was allocated Rs 16,335 crore ($2.3 billion) that year, nearly 23% less than its demand of Rs 21,101 crore ($2.9 billion).

Underfunding over the years, along with the Centre’s failure to pay for filling vacancies across the cadres engaged in nutrition services, can lead to systemic inefficiencies in fund utilisation.

When the government made advance estimates for what might be required in 2019-20, it raised the allocation for Anganwadi Services by 18% over the amount actually spent on the scheme in the previous year, data from the 2020-21 budget show. However, this allocation was reduced by around 11% (Rs 17,705 crore or $2.5 billion) when the government revised its estimates after six months into the fiscal year to align with expenditure trends. This indicated that the increased funds could not be utilised.

Besides shortage of funds, how money is spent is also crucial. The crowding of spending in the last three months of the budget year, as several studies have reported, must be avoided. “A rush of expenditure, particularly in the closing months of the financial year, shall be regarded as breach of financial propriety,” the January 2020 guidelines of the finance ministry on timely spending stated.

Persisting vacancies in ICDS

There are staff shortages in the cadres required for the delivery of nutrition interventions: The latest set of estimates, submitted to the Lok Sabha in November 2019, show that 5.63% of sanctioned posts for anganwadi workers and 7.85% for anganwadi helpers are vacant across India.

The maximum vacancies for AWWs are in Bihar (14.3%) and Delhi (13.8%), followed by West Bengal (10%), Uttar Pradesh (9.6%) and Tamil Nadu (8.8%). The situation is worse for anganwadi helpers--the worst performers are Bihar (17.5%), West Bengal (15.7%), Uttar Pradesh (13.4%), Tamil Nadu (11%) and Punjab (8.8%). Kerala and Himachal Pradesh are among the states with the fewest vacancies.

The proportion of vacancies is much higher in sanctioned posts for child development project officers (CDPOs) and lady supervisors (LSs). The CDPO is in charge of one block or 125-150 anganwadi centres, while the LS is in charge of 25. Their availability is essential for the proper implementation and monitoring of the programme.

But, as of March 2019, upto 30% of CDPO posts and 28% of LS posts lay vacant across the country, as per data submitted in Lok Sabha in June 2019. CDPO vacancies are highest in Rajasthan (64.5%), followed by Maharashtra (55.2%), West Bengal (51.9%), Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh (both 49.5%). The states with a high proportion of LS vacancies are West Bengal (67%), Bihar (48.2%), Tamil Nadu (44%), Uttar Pradesh (43%) and Tripura (42.4%).

High burden of salary, honorarium on states

The change in the Centre’s contribution to salaries under ICDS affects how human resource shortages are addressed. In December 2017, the cost-sharing ratio between the Centre and states for select salaried staff under ICDS, including CDPOs and LS, was revised from 60:40 to 25:75. Fiscally weaker states may not have the resources to recruit a sufficient number of regular workers against sanctioned ICDS posts.

As the new payment rates are also deemed inadequate, states have been providing additional honorarium to AWWs and AWHs: Haryana (Rs 7,286-Rs 8,429), Madhya Pradesh (Rs 7,000), Tamil Nadu (Rs 6,750) Delhi (Rs 6,678), Telangana (Rs 6,000) and Karnataka (Rs 5,000) give the highest additional compensation to AWWs.

For anganwadi helpers, the states offering the highest additional honorarium are Tamil Nadu (Rs 4,275), Haryana (Rs 4,215), Goa (Rs 3,000-6,000), Telangana (Rs 3,750), Delhi (Rs 3,339) and Madhya Pradesh (Rs 3,500).

Not only are anganwadi workers underpaid but their overburdened schedules and absence of capacity strengthening also adversely affect the quality of service. This implies a need for a significant increase in fiscal support to states.

13 February 2020

13 February 2020