Mental illness: Stigma, taboo or confusion?

When the word ‘mentally ill’ or ‘depressed’, is uttered various images are conjured in one’s mind but most of all it is a topic that people generally want to avoid. Of course, adding to this is the confusion around mental health and stigma surrounding it. The judgmental attitude towards the mentally ill does not help matters rather it perpetuates long standing biases. Even in the health sector, mental health is considered as the ‘elephant in the room’[1]. To understand some of the developments around mental health that have taken place in India, it would vital to track the stages of progress it has made since the time the first Mental Health Act was brought out in 1987. This Act had various issues as it was not focused on patients’ rights and had an overemphasis on mental institutions/asylums. After almost 30 years, in 2017, the government passed the Revised Mental Health Bill which provided a greater sense of dignity, rights and assistance to the mentally ill[2]. Prior to that, India’s first National Health policy in August 2015 provided access to good quality treatment, to mentally ill people especially the poor. These were landmark developments albeit slightly delayed and after years of struggle by mental health activists and doctors.

Statistics on the mentally ill in India: Startling or usual?

As per the World Health Organisation (WHO), 7.5 per cent of the Indian population suffers from some form of mental disorder.

India accounts for nearly 15 percent of the global mental, neurological and substance abuse disorder burden with a’ treatment gap’[3] of over 70 per cent. WHO also predicts that by 2020, roughly 20 per cent of India will suffer from mental illnesses[4].

According to the Ministry of Health & Family Wefare (MoHFW), India needs 13,000 psychiatrists. To achieve an ideal ratio of psychiatrists to population would be about 1: 8000 to 10,000 but currently it has just about 3,500. This is about one psychiatrist for over 2 lakh people. In 2011, there were 0·301 psychiatrists, 0·166 psychiatric nurses, and 0·047 psychologists for every 100,000 mental-disorder patients in India. The number of psychiatric beds per 10,000 patients in psychiatric hospitals was 1·490, and in general hospitals 0·823[5]. Similarly, a NIMHANs study[6] commissioned by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in 2015-16 found that 13.7 percent population has been suffering from mental illness. The burden of mental disorder is highest among teenagers and young adults of the 15 – 44 years age cohort. This cohort is also the most economically productive sector and hence has a direct impact on the economy. Amongst corporate workers, 4 out of 10 professionals suffer from depression and anxiety where 55 percent are below 30 years and 25 percent are between 30-40 years. Presenteeism[7] versus absenteeism[8] is on the rise and another reason for low productivity at the workplace[9]. Further, persons with mental disability are placed at the bottom of the pyramid thus leading to further invisibility in the health sector.

The National Mental Health Programme: Overlooked and underfunded

Since mental health falls in the Concurrent List both the Central and State government are responsible and can make laws around it. Mental disability was for the first time included in the NSSO 58th Round July-December in 2002 wherein long term mental illness was considered a disability. The Parliament passed the Mental Health Care Bill in 2017 replacing the older Act since 1987 which stigmatized and infantilized mental health. A look at the national level programme which caters to communities at both the State and Central is the National Mental Health Programme(NMHP) and listed under the Tertiary programmes section in the Central government budget, gives an adequate picture on what the government has envisaged for the mentally ill population.

The NMHP envisages a community based approach to the problem, which includes (a) training of the mental health teams. (b) increase awareness about mental health problems (c) provide services for early detection and treatment and (d) provide valuable data and experience at the level of community in the State and Centre for future planning, improvement in service and research[10].

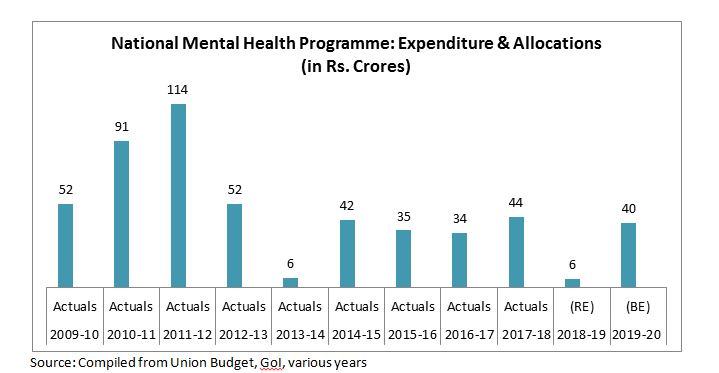

Coming to the budgetary aspects of the Programme, allocations and expenditure in the last 10 years do not show a very promising picture as seen in Table 1. Except for the year 2011-12, where the expenditure for the NMHP was Rs. 114 crores, there has been a sharp decline from 2012-13 onwards. This trend in allocation has remained almost stagnant at an average of Rs. 40 crore from 2012 onwards with a drastic reduction in 2013-14 toRs. 6 croreonly. With the annual health expenditure of India being 1.15 percent of the grossdomestic product, and themental health budget less than 1 percent of India's total health budget[11], one can only wonder how much budgetary priority the NMHP would get.

Table 1: National Mental Health Programme: Expenditure and Allocations 2009-10 to2019-20

Tackling the ‘elephant in the room’

-Despite the revision of the Mental Health Act and growing media and celebrity coverage on the problem more so in the present era of virulent social media, there is a long way to go. Firstly, understanding the law and what it entails for the poor should be the primary step. Since, the law is largely pro-rights and pro-poor, there is a lot of scope for State and local governments to involve CSOs wherever there is a gap.

-Secondly, integrating mental health care with primary health care would help remove the hesitancy of patients accessing mental health care services. It is assumed that the cost for mental health is a prohibiting factor for patients to take treatment; however, if one estimates annually the cost implications of treating a person with depression, it would amount to the same as someone being treated for blood pressure or diabetes. Moreover, according to the new Act, the government is mandated to provide mental health servicesfree of cost at primary health centres.

-Thirdly, the existing number of mentally ill persons itself is a number that is inaccurate for being severely underreported since India has a large ‘treatment gap’. For this, large scale awareness on mental health in educational institutions and work places could help in breaking some of the stigmas attached to seeking treatment.

-Last but not the least, adequate budgetary resources not just for mental health institutions are required, but rather increased budgets for the NMHP would serve the purpose of mental health care reaching to poor and marginalized communities.

[1]https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/beth-saward/mental-health-stigma_b_3154860.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAABJV3BuvUvnm46CULXqKGPlc9lH-XBEG7a5LQVWyP6qmxYqtP_62k38MjE_HzfCpDx84oDAnHO7jrMY1iYI2Klg4bcNyxvZ_RuLIicDe4KZWWT0cdCP2bxVc3kBsxiI93rhMkLEEj8LletTYA2zUcUjI6lFHkOQ6LxcLKv1xPiAh

[2]https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/india-has-new-mental-healthcare-law-and-heres-all-you-need-know-about-it-59404

[3] Treatment gap is the number of individuals (expressed as a percentage) with a mental illness who need treatment but do not receive it.

[4] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/mental-health-in-india-7-5-of-country-affected-less-than-4000-experts-available/articleshow/71500130.cms?from=mdr

[5] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/are-you-a-depression-patient-dont-look-to-this-years-budget-for-hope/articleshow/62742681.cms?from=mdr

[6]http://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/Docs/Report2.pdf

[7]Presenteeism or working while sick can cause productivity loss, poor health, exhaustion & workplace epidemics. In Singapore, the term refers to the practice of employees staying in the office even after their work is done to wait until their bosses leave.

[8]https://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/the-break-out-zone/mind-above-all-else/story/366558.html

[9]https://www.bbc.com/news/business-47911210

[10]Union Budget, various years, Expenditure Vol II., Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Department of Health & Family Welfare

[11]http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org/article.asp?issn=0019-5545;year=2019;volume=61;issue=10;spage=650;epage=659;aulast=Math

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author, and don’t necessarily reflect the position of CBGA. You can reach Trisha Agarwala at

tr******@gm***.com

.

3 December 2019

3 December 2019