During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in 2020, National Commission for Women (NCW) received 23722 complaints of crimes against women, the highest in the past 6 years. Even before the pandemic, increased violence against women (VAW) between 2015-16 and 2019-20 was observed for more than seven States. The situation has only worsened over the months, as NCW recorded 1463 cases of domestic violence alone between January and March 2021.

If women are to be empowered and gender gaps to be bridged, addressing VAW should be at the top of policy formulation and implementation. A study highlights that a large number of survivors of VAW continue living in their abusive homes, often unaware of alternative safe spaces or not finding them viable. This is exacerbated by social pressures forcing women to remain silent. In line with the Sustainable Development Goals emphasising on eliminating VAW and under the purview of National Policy for Women 2016, it is high time to review what services are currently available to women in distress in India.

The Union Budget 2021 shows that several women-centric schemes have been rationalised. The bucketing of different schemes for women under the umbrella ‘Mission Shakti’ may prove counterproductive, as the budgetary allocation for these schemes has been declining over time. For instance, allocations under components Sambal and Samarthya under Mission Shakti, subsuming a large number of schemes designed for protection and empowerment of women have seen a reduction averaging 8.5 per cent.

With increasing VAW and very limited platforms of public services being available for women in distress, an increased focus on specific schemes against VAW becomes even more crucial. The Swadhar Greh (SG) scheme is one such initiative to provide shelter to women in difficult circumstance, including distressed homeless women – whether they are victims of violence, abuse, harassment or driven by poverty and / or old age.

Swadhar Greh: Origins and Objectives

The term Swadhar Greh refers to shelter home for women in distress. The SG scheme was formed after merging two earlier schemes: Swadhar, and Short Stay Homes (SSH). The merged scheme, targets all women victims of unfortunate circumstances as well as women in distress, including widows, destitute women and aged women. The facilities can also be availed by children accompanying women in these categories. The scheme provides temporary residential accommodation, food, clothing, medical facilities, vocational and skill up-gradation training, counselling and legal aid to women in distress.

The revised guidelines of the scheme proposed setting-up a SG in each district in the country with a capacity of 30 women, while big cities and large districts could establish more than one SG. The duration of stay in a SG for women affected by domestic violence is upto one year, while other categories of women can stay upto three years. Older women above the age of 55 can be accommodated for upto five years, post which they would be shifted to old-age homes.

Declining Budget and its Utilisation: Are women no longer in distress?

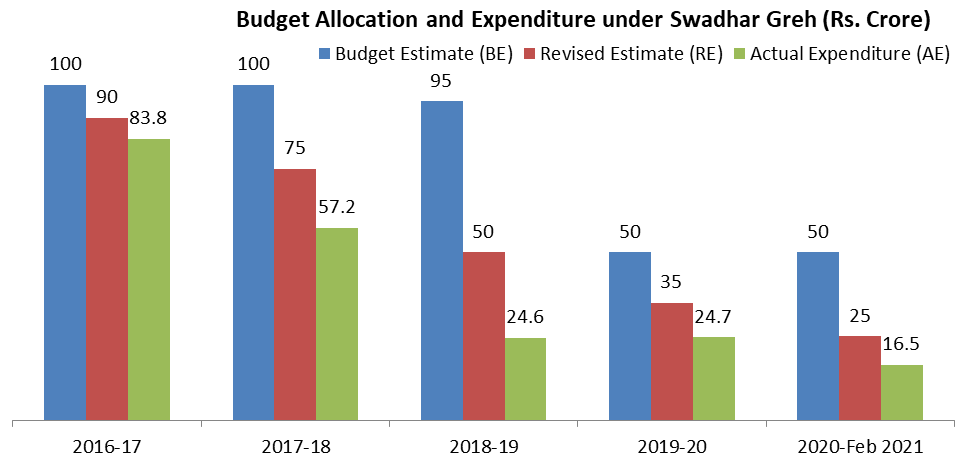

The funds under the scheme are released with a cost sharing ratio of 60:40 between the Centre and States (except for North Eastern & Himalayan States where it is 90:10 and for UTs, it is 100 per cent from the Centre with effect from 2016). The extent of original budget allocation, revised allocation and actual utilisation of funds under the SG scheme reveals the following.

Source: Press Information Bureau (PIB)

Budget allocations for the scheme have seen a decline over the last five years. In terms of absolute amount, the allocation has declined to Rs. 50 crore in the financial years (FY) 2019-20 and 2020-21 from Rs. 100 crore in FY 2016-17. In each of the financial years since 2016-17, the revised budget allocation under the scheme shows a downward trend, indicating less demand for fund or slash in budget due to low rates of fund utilisation. The actual expenditure reported was even less than the revised estimates in each of the years. If actual expenditure as a percentage of original budget estimates is considered, the extent of fund utilisation for the FY 2019-20 turns out to be just 50 per cent, dropping from 84 per cent in FY 2016-17 to 57 per cent in FY 2017-18. The situation for FY 2020-21 (upto February 2021) is even worse, even though this period has been more testing for women.

It has also been noted that allocations under recurring expenditures towards staff salaries and residents have undergone revisions and are not commensurate with the cost of living. Overall, the amount of budget allocated for the scheme is very low and the extent of fund utilisation of allocated funds reported by the Sates is also very low. Limited resources, coupled with under utilisation of funds exacerbate the situation on the ground. It was noted that the instalments released from the Centre to States under the scheme are often delayed, one of the reasons for these delays reported by the Union Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) was lack of receipt of utilisation certificates (UCs) from States on time. Looking at the trends of budget allocation and examining the extent of fund utilisation across States and UTs during 2016-17 and 2018-19, the following insights are worth highlighting.

Report Card: Extent of Funds Utilised against Funds Released under Swadhar Greh Scheme between 2016-17 and 2018-19

| Extent of Fund Utilisation | Extent of Funds Utilised against Funds Released during 2016-17 | Extent of Funds Utilised against Funds Released during 2017-18 | Extent of Funds Utilised against Funds Released during 2018-19 |

| >= 90 per cent | Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, West Bengal, Chandigarh, Delhi and Puducherry | Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Tripura, Jammu and Kashmir and Puducherry | Arunachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Manipur, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Tripura and Jammu & Kashmir |

| >= 80 – 89 Per cent | Madhya Pradesh (81), Odisha (88), Sikkim (83), Tamil Nadu (87) and Telangana (85) | Andhra Pradesh (89), Odisha (85) and Delhi (83) | Sikkim (86) |

| <80 Per cent | Andhra Pradesh (77), Jharkhand (45), Rajasthan (43) and A & N Islands (50) and Jammu and Kashmir (8) | Madhya Pradesh (78), Punjab (18), Rajasthan (18), Telangana (70), Uttar Pradesh (18), Uttarakhand (37), West Bengal (76), A & N Islands (78) and Chandigarh (78) | |

| States / UTs with utilisation rate is either ‘zero’ or data not available | Bihar, Goa, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Daman & Diu and Lakshadweep | Bihar, Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Daman & Diu and Lakshadweep | Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Goa, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Mizoram, Nagaland, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, West Bengal, A & N Islands, Chandigarh, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Daman & Diu, Delhi, Lakshadweep and Puducherry |

Source: Compiled from data presented in Open Budgets India Portal, available at: https://schemes.openbudgetsindia.org/scheme/sg/total-funds-released

A number of States/UTs like Arunachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Manipur, Tamil Nadu and Tripura reported more than 90 per cent utilisation of allocated funds during FYs 2016-17, 2017-18 and 2018-19. Since the amount allocated under the scheme is low, the utilisation rate seems to be high for these States. However, States like Bihar, Goa, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Odisha have been reporting comparatively low extent of fund utilisation. A crucial message emerges from the fact that data on fund utilisation for many States and UTs are not readily available in the public domain and some states even reported ‘zero’ utilisation of available fund. Over the years, there has been a reduction in budget allocation in absolute terms and low levels of fund utilisation under the scheme raises a number of serious concerns pertaining to the demand and supply mismatch.

It is also important to note the total number of SGs present in India. As on December 2020, there were 362 SGs, down from 559 in 2017-18 and 417 in 2019-20 (Press Information Bureau (PIB) and Annual reports for different years of the MWCD). This was despite the sanction of 51 new SGs in 2019-20. Based on the guidelines, each of the 736 districts in India should have a SG; however, the existing numbers of SGs cover only 50 per cent of the required number. In terms of the number of beneficiaries of the scheme, there has been a sharp decline from 16530 to just 7785 between 2016-17 and 2020-21. This may also be one of the reasons for decline in budget allocation for SG scheme.

Partial coverage of SGs both in terms of number and beneficiaries, coupled with a declining budget allocation in times of increasing VAW is a serious concern that needs immediate attention from various quarters.

The way forward

The concept of shelter-homes has been in place for over 20 years now, but a decline in the number of SGs can either mean that ‘everything is fine’, or that there is a serious lacuna in the system. There has been a continuous decline in budget allocation for SG and the existing allocation has not been utilised fully. Does this mean that that there is no longer a need for these institutions and that women in India are no longer in distress? We know that this is not a correct depiction of the situation, so what conclusion can we derive? That the voices of the elderly women and the victims remain unheard in the policy corridors and the SG scheme is not being paid due attention, possibly as it does not seem to serve electoral purpose.

The way forward should be increasing policy focus on SG and related schemes, with adequate budgetary allocations. Given the increase in VAW, the capacity and coverage norms of SGs should be increased from just 30 women and one shelter home per district. To this effect, a study suggests exploring the use of working women’s hostels / temporary rent support. This study also estimates that 1667 more SGs with 30-beds capacity will be needed to accommodate more than just 12890 women, which is important given the incidents of increase in VAW. Increasing unit costs, construction aid for more SGs, regular audit are a few suggestions worth noting.

Women empowerment must not just be a term or buzzword, it needs to become a reality. The government has a herculean task at hand, when the scheme designed to help women in distress is itself in distress!

Authors work with Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA), New Delhi. Views expressed are of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the position of CBGA. You can reach them at

an****@cb*******.org

and

ni*******@cb*******.org

.

15 June 2021

15 June 2021