As one of the 193 United Nations Member States to adopt the Sustainable Development Goals, India is committed to the UN pledge to “leave no one behind.” A crucial aspect of achieving these ambitious Global Goals — which include providing quality education for everyone, everywhere — means equipping the country’s youths with access to digital technology. Yet, with the pandemic shuttering schools across the nation, online tools for students have become even more critical — and scarce.

“In our school, online classes started in March 2020, but I started attending them only in August. I did not know classes had started,” says Nidhi, a high school student from a girls-only public school in southeast Delhi.

Another student, Chandan, ultimately learned about the online classes after a classmate passed along his phone number to the teacher. Only then was Chandan included in the chat group where his teachers were sharing everything related to online classes. Last September he started studying again, nearly five months after his school had launched the online platform.

Both Nidhi and Chandan lost precious months of learning. Their stories exemplify a growing gap in India between children who have access to online classes and those who don’t.

THE CHALLENGE OF REACHING EVERY STUDENT

Our latest survey with the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) examined the experience of children attending secondary education in government and government-aided schools in Delhi since the start of the pandemic in 2020.

As a precaution against the spread of COVID-19, the Government of Delhi suspended in-person classes in all schools starting April 1, 2020. In the first communication on school closure and online courses, the Delhi Directorate of Education also developed a plan to implement remote learning activities. The information technology (IT) branch of the government was tasked with reaching students through SMS text messages and sharing details about online classes.

Another Delhi government circular issued in July 2020 instructed all government and government-aided school principals to disseminate information on school closure and online classes. It was to be sent to teaching and nonteaching staff, parents, and students through members of the School Management Committee, mass or individual SMS facilities, phone calls, and the like.

But contacting the estimated 320 million school-aged children in India — one of the largest populations of youths in the world — is an enormous undertaking.

And as our survey uncovered, many children, including Nidhi and Chandan, were not reached.

DIFFICULTIES SWITCHING FROM IN-PERSON TO ONLINE

In the shared physical space of schools, teachers and students are naturally connected. Pupils stay in the loop of developments relating to their curriculum, class logistics, extracurricular activities, and anything else they need to know. They can always reach out to their peers, friends, or teachers for any information they missed. But what happens when the physical space is no longer accessible and all communication moves online?

From our interaction with students, it appears that there was no dedicated website or helpline available to provide them with the necessary information. In many cases, WhatsApp groups were reported to be the only means of communication. No one-on-one interaction was available. In some cases, teachers sought the help of the class representative to coordinate with students.

WhatsApp groups also remained inaccessible to many students who didn’t have adequate access to a phone, as revealed in our survey. In many cases, the parent who owns the phone needs it for work. That means that pupils have access only in the mornings or evenings. One child reported that he had to go to his aunt’s house at night, which was quite far from his own home, to use her phone. Hence, he frequently missed communications from his teachers.

CREATIVE ALTERNATIVES TO REACH STUDENTS

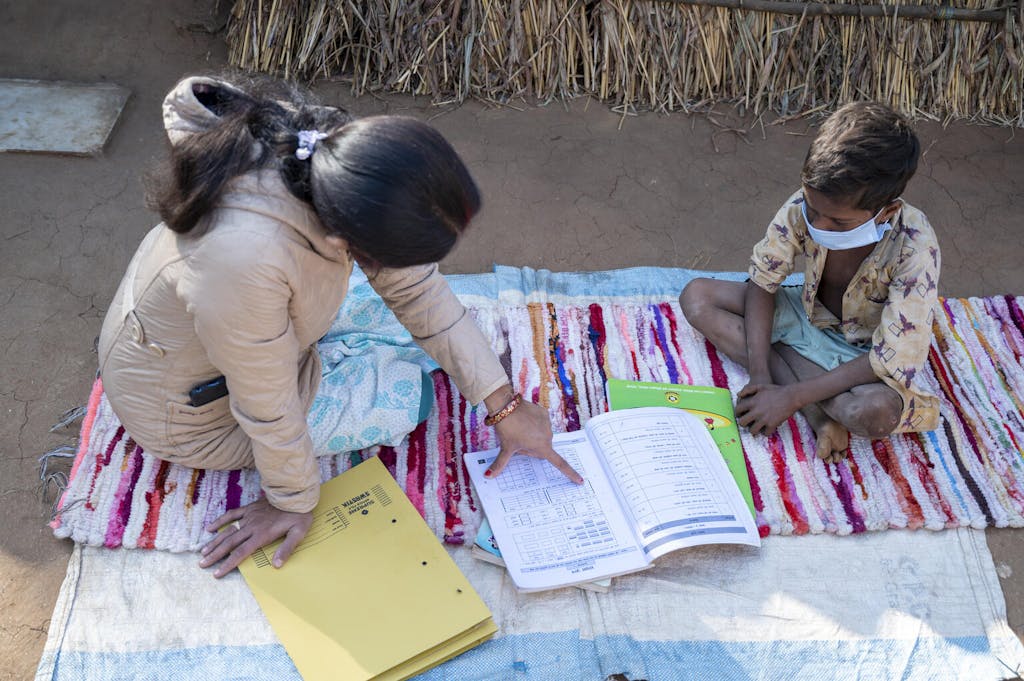

These anecdotes reveal that there is no comprehensive digital infrastructure in place. In the absence of access to devices and Internet connectivity, other options have emerged. Television, radio, SMS, interactive voice-based communication, and even door-to-door contact are a few examples. State governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have tried these alternatives with varying degrees of success. In the Jhabua district of Madhya Pradesh, teachers held open-air classes after going door-to-door to invite students when COVID-19 receded. Teachers in Chhattisgarh tried “loudspeaker schools” and Bluetooth-enabled audio lessons through simple phones.

The experiences show that schooling during a pandemic cannot rely on a single communication channel. It takes a creative combination of high-tech, low-tech, and even “no-tech” approaches to retain every child in the public education system.

Even before the pandemic, there was global concern about the growing digital divide and so-called learning poverty that vulnerable children, especially girls, are facing. In light of that, UN Secretary-General António Guterres launched the first-ever Roadmap for Digital Cooperation last year to address this widening, worldwide gap.

But COVID-19 has only worsened the situation. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) found that some 168 million children across the globe lost a year of schooling in 2020 due to the shutdowns.

What our study revealed is that, as a result of the pandemic, a lack of access to digital technology has become the most urgent hurdle to overcome when it comes to educating India’s children. Until schools open, without rapid action, the consequences for the children’s well-being and future could be devastating.

Protiva Kundu leads research on government financing of education at Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA).

Shruti Ambast joined CBGA as a Policy Analyst from September 2019. She is currently working on issues of public finance in the nutrition sector.

This story was provided by Southern Voice, a network of think tanks in Africa, Latin America, and Asia that amplifies local data and research in support of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The UN Foundation partners with Southern Voice to highlight local SDG stories from around the world.

Featured Photo: Vinay Panjwani/ UNICEF

27 August 2021

27 August 2021