Lately, you might have come across two terminologies - cesses and surcharges - being discussed frequently in the media. It is possible you may have even wondered if cesses and surcharges levied by the Central government are just like any other tax, what all the fuss is about.

It is true that cesses and surcharges are, in some sense, similar to regular taxes (such as income tax or customs duty). They are similar because both cesses and surcharges are usually imposed as a tax on tax – for instance, the education cess is an add-on to the Income Tax. Thus, for taxpayers additional cesses and surcharges are no different from additional taxes as both results in an additional tax outgo.

But there are several reasons why they are different from regular taxes. The most important reason that makes cesses and surcharges different from regular taxes is that the Centre needs to share with the States the revenue earned through regular taxes. On the other hand, as per the provisions of Article 271 of the Constitution, the revenue earned by the Centre from cesses and surcharges need not be shared with States.

Cesses and surcharges pose a problem for States’ finances

It is for this reason that excessive reliance by the Centre on cesses and surcharges for generating additional revenue can become a cause of concern for States. If, for instance, the Centre earns additional revenue by increasing tax rates then that is shareable with the States. An increase in revenue earned by the Centre in this way helps States too as they also get a part of the additional revenue. But if the same additional revenue is earned through by imposing surcharges or cesses then States do not get a share of that. As a result, even though the total revenue earned by the Centre increases, the States do not gain anything. This should be seen in the context of the fact that it is the States that have the major expenditure obligations and central tax devolution is a major source of finance for carrying out these responsibilities. Therefore, the Centre earning extra revenue by levying cesses and surcharges exacerbates the vertical imbalance between the Centre and States.

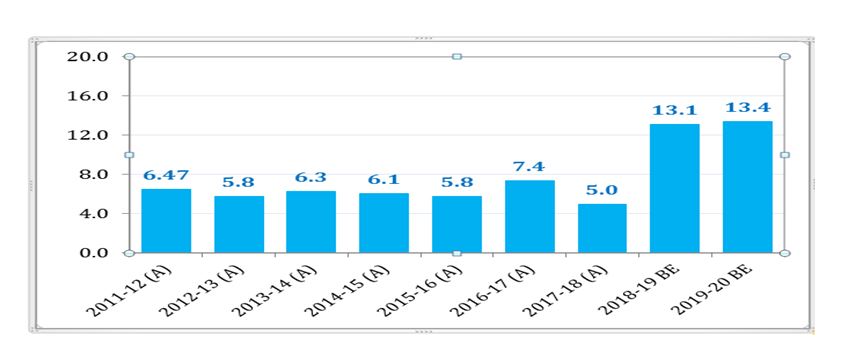

Indeed, in the last few years, the share of cesses and surcharges in the Gross Tax Revenue (GTR) mobilised by the Centre has gone up sharply.

Table: Cesses and surcharges as proportion of Gross Tax Revenue

GST cess is not included.

A - Actual; BE - Budget Estimate; RE – Revised Estimate

Source: Isaac Thomas, et al and Union budget documents

One of the reasons for this is that a bevy of new cesses and/or higher surcharges has been levied by the Centre during this period. For instance, in the budget 2019-20, the Central Government levied two new surcharges on super-rich individual taxpayers, and increased the rate of existing surcharges on Corporate Income Tax.

However, it also needs to be noted, the use of cesses and surcharges by the Centre for mobilising additional revenue for itself is nothing new. Cesses and surcharges have been in existence since the British Raj and have been used extensively by different governments since then.

Why the problem is somewhat different and even more serious today

The obvious question then is if cesses and surcharges have been used earlier as well what is different this time around. The situation today is indeed different because the issue is no longer only about the Centre relying on tools to augment tax revenue so that it does not have to share with States. The distinctive aspect about the recent past is that cesses and surcharges have been increased even while central tax rates have been reduced.

For instance, in the 2017-18 budget while the Centre reduced the tax rate of incomes up to Rs. 5 lakh from 10 per cent to 5 per cent, it levied a surcharge on incomes above Rs. 50 lakh to counter the resultant revenue loss. Similarly, in the 2018–19 budget even while excise duty on petrol was reduced by Rs. 9 per litre, the road cess was increased by an equivalent amount.

Lower tax rates not only reduce the revenue earned by the Centre, it also reduces the amount devolved to/received by States. While the Centre has been using cesses and surcharges to make up for its loss of revenue, resorting to these tools do nothing by way of increasing resources received by States. In short, the situation is even graver today for States because it is not just that the Centre is not required to share the additional revenue earned through cesses and surcharges, but also that the pool of tax revenue to be shared with States itself is shrinking. As some analysts have noted, the problem today is that “surcharges and cesses have become a mode of shrinking the divisible pool of taxes and make reduction in basic tax rates revenue neutral for the centre”.

What is to be done

The situation is all the more problematic in light of the fact that States’ own sources of revenue are under stress because of less than adequate overall Goods and Services Tax (GST) (and hence State GST) collection. Therefore there is a dire need to curb the use of cesses and surcharges. As an immediate remedy, steps need to be taken to ensure that cesses are levied for limited duration, as recommended by the Sarkaria Commission way back in 1983. In the longer term, as suggested by some analysts, Article 271 of the Constitution needs to be amended to ensure that “cesses that continue for more than two years should compulsorily be shared with the states”.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of CBGA. You can reach Malini Chakravarty at

ma****@cb*******.org

29 November 2019

29 November 2019