The inclusion of rural housing scheme has inflated the gender budget even as actual houses built for women have fallen

Budget 2018-19 failed to match the accompanying rhetoric on women empowerment, despite a pink-colour themed Economic Survey that dedicated a chapter to son preference. There were admittedly some sops to women: a cut in provident fund contribution, and 80 million free gas connections for poor women. Yet, a closer examination of allocation of funds reveals that the budget had very little for women in it.

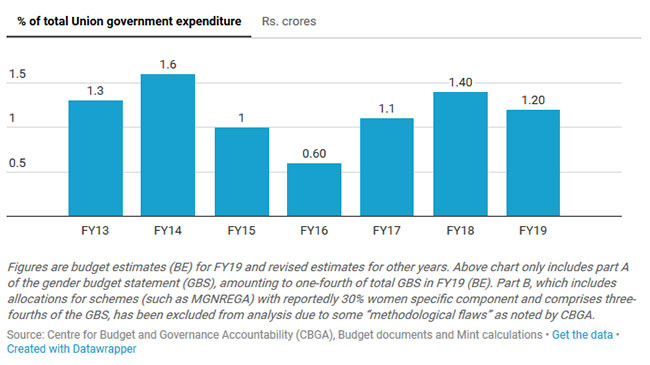

Budgetary allocations for “100% women-specific programmes” in 2018-19, as listed in Part A of the Gender Budget Statement (GBS), declined.

The gender budget is organized in two parts, A and B. Our analysis excludes Part B, which lists schemes where 30% of funds are aimed at women, because not all ministries have provided a rationale for the proportion of scheme expenditures included in it, as noted by the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) in a recent report.

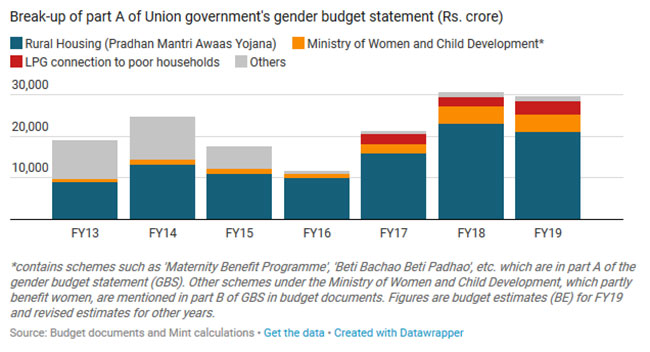

Even the figures mentioned in Part A might be over-estimates. The biggest component of GBS (Part A) in recent years has been the subsidized rural housing programme: the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana -Gramin (PMAY-G), formerly called the Indira Awaas Yojana.

No visible increase in government spending for women

Allocations under gender budget (part A only, where 100% of allotted money is aimed at women)

However, the PMAY-G is not targeted specifically towards women. The scheme guidelines do not specify any fixed amount of money or share of houses to be granted to women, though female-headed households without a male member, or households having a single girl child, are given preference as beneficiaries. PMAY-G gives Rs1.2 lakh assistance for building pucca (permanent) houses in plains and Rs1.3 lakh in hilly and difficult terrains.

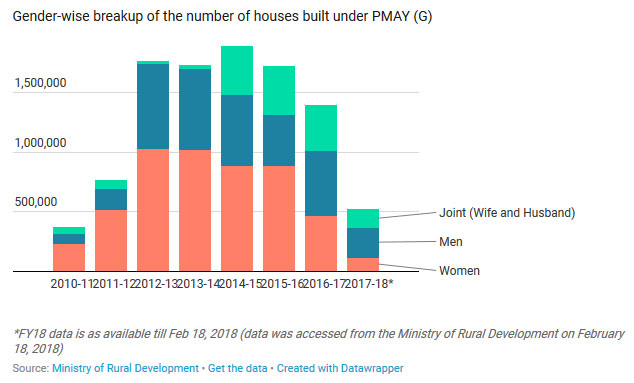

Though budgetary allotment for this scheme has shot up in recent years, houses built for women have fallen, both in absolute numbers and as a share of total houses built.

Rural housing increasingly an important component of gender budget

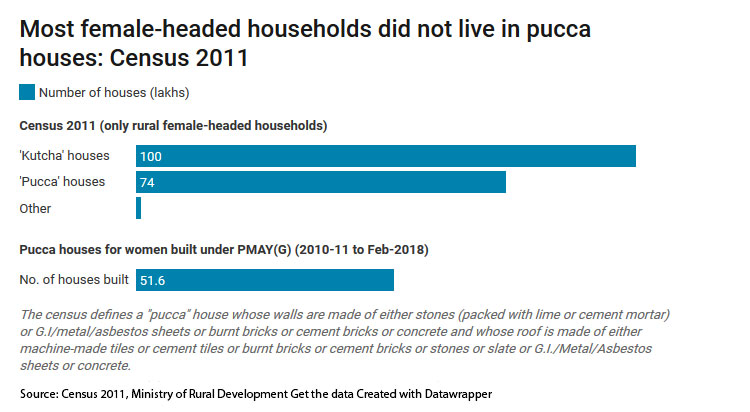

Lack of demand is most probably not a reason for the fall in houses built for women. Census 2011 puts the total number of female-headed households in rural India at about 17.5 million. Out of them, 62%, or about 10 million households, live in kutcha (temporary) houses. Despite this apparent need for pucca houses, only about 5 million houses for women have been built under PMAY-G since 2010-11, according to data retrieved on 18 February.

It’s thus misleading to include entire allocation for PMAY-G in gender budget especially when the number of houses built for women have been falling. Both centre and states need to take accountability for the slow completion rate of houses and disbursal of funds.

Meanwhile, the government has increased allocation for the ministry of women and child development (MWCD) by a respectable 10% in 2018-19 compared to 2017-18 (revised estimates). Nevertheless, spending on MWCD as a share of total budget remains below the levels seen in 2012-13 and 2013-14, the last two years of the previous Congress party-led government.

This is partly due to the 14th Finance Commission award since 2015-16, which increased tax devolutions to states. To compensate, the centre has cut back on centrally sponsored schemes, many of which involve social sector spending.

While the government has increased allocation for some schemes under the MWCD, such as the maternity benefit programme, Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao etc., a lot will depend on implementation. To illustrate, of the Rs400 crore initially allotted for maternity benefit in 2016-17, less than a fifth, i.e. only Rs75 crore, was actually spent that year. The maternity benefit scheme provides a cash assistance to mothers for their first delivery to compensate wage loss.

Spending on anganwadi services, or the “core Integrated Child Development Services”, has increased only marginally.

Construction of women-owned houses has fallen

Anganwadi services are the main mechanism by which the government administers programmes to improve the health and nutrition of pregnant women, nursing mothers and children up to six years of age.

States have also neglected their duty in expanding this important programme. Some have a considerable deficit in the number of operational anganwadi centres as against the number sanctioned.

In light of the above shortcomings, budget 2018’s promise of being women-friendly appears exaggerated.

26th February 2018

26th February 2018