The allocation for the ministry of health and family welfare (MoHFW) in Budget 2019 is likely to increase from Rs 52,800 crore (budget estimates) in the current financial year 2018-19 to Rs 59,039 crore in the next financial year (2019-20), an increase of 11%, according to the medium term expenditure projection statement presented to the Parliament in August 2018 by the ministry of finance.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) is also likely to increase allocation for the government’s flagship programme, National Health Mission (NHM), by 17% in the coming year from Rs 30,634 crore in 2018-19 to Rs 35,962 crore in 2019-20, an increase of Rs 5,328 crore.

The statement also shows that the allocation for tertiary care (Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana) is likely to be reduced from Rs 3,825 crore in 2018-19 to 3,170 crore in FY 2019-20, a decline of 17%.

Why public health infrastructure is important

The projected allocations for the health sector indicate that addressing issues on public health infrastructure is slowing since the central government is likely to increase allocation of resources for primary and secondary healthcare at the cost of tertiary care.

A number of services are not available at public health facilities due to the low level of public expenditure on health. Moreover, the quality of services available at public health facilities is in poor state. As a result of inadequate and poor quality services at public health facilities, patients are bound to seek services from private health facilities, which increases out-of-pocket expenditure.

An example: Institutional birth rate increased from 47% in 2014 to 78.9% in 2016, according to the National Health Profile 2018. In spite of the huge leap in the institutional birth rate, only 52% is happening at public facilities while around 48% childbirths take place at private health facilities.

With the introduction of user fees at public health facilities, it no longer remains free-of-cost. Out-of- pocket expenditure has increased by 16% between 2014 and 2016, according to datafrom the World Health Organization.

The current status of health infrastructure in India

If we go back to what the government had promised in its manifesto, the assurance was to increase public health spending to address shortages of infrastructure and human resources for equitable access and reduce out-of-pocket expenditure. However, consistent neglect of priority in public provisioning has led to acute shortages in health infrastructure including human resources at various levels.

There is a shortfall of 32,900 sub-centres (catering to a population of 5,000), 6,430 primary health centres (PHCs, catering to 30,000 people) and 2,188 community health centres (CHCs, addressing health needs of 80,000-120,000 people) in rural areas, as on March 31, 2018, according to Rural Health Statistics (RHS) Bulletin, 2017-18 .

Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal had shortfall in health facilities. As many as 37,950 sub-centres, 980 PHCs and 19 CHCs operate out of rented buildings.

Only 7% of the currently functioning sub-centres, 12% PHCs and 13% CHCs are functioning as per Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS).

Even after the implementation of Swachh Bharat Mission (Clean India Mission), 42% sub-centres, 18% PHCs and 12% CHCs do not have toilets.

The shortage of infrastructure is worse in tribal areas where the shortfalls are reported to be 5,935 sub-centres, 1,187 PHCs and 275 CHCs, according to the RHS 2017-18.

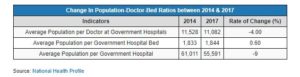

The population-doctor ratio in India was 11,082:1 in 2017 in government hospitals, 25 times higher than the WHO recommendation of 25 professionals per 10,000 population.

While the population-doctor ratio at government hospitals and the population-government hospital ratio reduced by 4% and 9%, respectively, the gap is still huge compared to WHO norms.

Similarly, the population-bed ratio increased from 1,833 to 1,844 between 2014 and 2017, according to the National Health Profile as against the bed-population ratio of 1:1,000 based on the Mudalier committee recommendations.

Almost 3,667 sanctioned positions for doctors are lying vacant at district hospitals. The figure for sub-divisional hospitals is even higher at 7,144.

The shortfalls of sanctioned positions of para-medical staff both at the district and sub-divisional hospitals were reported to be 3,011 and 7,456, respectively.

The shortfall of female health workers (7,194) and male health workers (104,318) in sub-centres, 10,907 auxiliary nurse midwife (ANMs) at SCs and PHCs, 3,673 doctors at PHCs, and 18,422 specialists at CHCs show the extent of human resources shortages.

Despite the shortage in health personal, the government made it clear that Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and ANMs will continue to work as casual workers in National Health Policy, 2017.

There are regional disparities in health infrastructure as well: Although more than two-third of the population (69%) live in rural areas, availability of bed is more (151,585) in urban hospitals compared to rural hospitals, according to data from the National Health Profile .

29 January, 2019

29 January, 2019