The educational landscape of India has been transformed by a series of developments in new-age pedagogies. Use of technology in education is one of the milestones in this direction. This has resulted in opening up of number of Edtech (Education and technology) industries in the country.

Accelerated growth amid pandemic

Growing internet penetration and availability of cheaper smartphones with affordable data packages created a demand for quality education through various learning platforms. Before the pandemic, the digital adoptions were taking place largely through Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), distance education and job search.

After the outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic, with closures of institutions and wider adoption of online education, the demand for Edtech products increased multi-fold. As a result, the whole Edtech sector witnessed an exponential growth in terms of user base, inflow of investment and acquisitions.

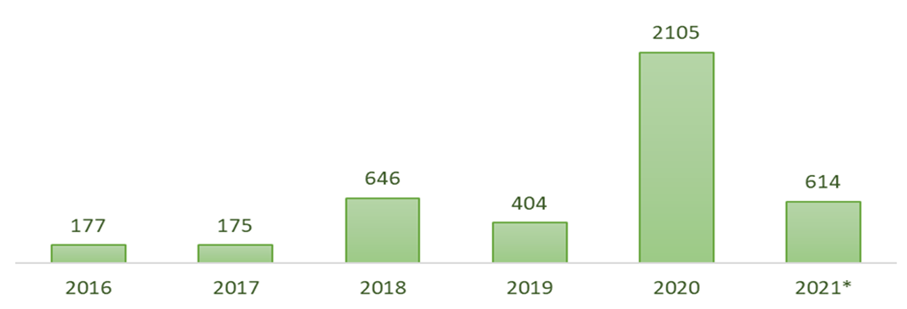

In 2016, while the online education market had 1.6 million paid users, there is a projection of 9.6 million users by 2021 (KPMG, 2019). The extent of investment growth can be imagined with the following figures (See figure). Against US$ 1.4 billion investment in the previous four years, the sector saw an investment of US$ 2.1 billion alone in the calendar year 2020.

Figure: Edtech investment in India (US$ Million)

Note: * as on April, 2021;

Source: RBSA Advisors

According to the Indian Private Equity and Venture Capital Association (IVCA) and the PGA Labs report, India’s education sector might witness a growth to US$ 225 billion by 2025. As Edtech companies are all pouncing on the opportunity to gain the biggest market share, there could be a surge of Edtech companies in the sector.

At present over 4,530 Edtech start-ups are operating in India, out of which 435 have come about in the past 24-months alone. These companies are largely providing their services under five major fields of education – School education, Skill education, Higher education, Preparation for competitive examinations and learning of non-academic subjects (e.g, spoken English). While skill education and online certification is the major constituent of the Edtech market, Edtech as supplement of school education received huge traction in the last couple of years. As per a KPMG report, education offerings for classes 1 to 12 are projected to increase 6.3 times by 2022 from the base of 2019.

Because of the growth, the Edtech industry has garnered the interest of global investors. India has emerged among the top three countries in the world after China and the USA to get venture capital funding in the Edtech sector. The industry has attracted private equity investments of US$ 4 billion in the last five years. In this connection, the most widely known and high valued Edtech companies in India are Byju’s and Unacademy.

From 2015 till March 2020, Byju’s had garnered 50 million free users on the platform, with 3.5 million paid subscribers and, in the last few months, the number has gone up to 70 million free users of which 4.7 million are paid subscribers. Byju’s and Unacademy have raised capital worth US$ 2.32 billion and US$ 354 million respectively in the year of the pandemic (IVCA-PGA Lab report, 2020).

However, except these few Unicorns such as Byju’s, Vedantu, Unacademy, and Toppers, many of the fresh start-ups are finding it difficult to sustain themselves in the market either because of inadequate capital or poor business models. Overcrowding of start-ups with similar kinds of services creates confusion among users and therefore, they finally ending up choosing those companies which are there in the market for a while.

Government initiatives

One of the major factors behind the growth of Edtech companies is the dissatisfaction with the current education offerings in traditional classrooms. In the last few years governments, both Union and States are also endorsing use of technology in the delivery of education. The Government of India is promoting online learning in the country through initiatives like the SWAYAM (study webs of active learning for young aspiring minds), an online learning platform run by the Ministry of Education (MoE). SWAYAM has a repository of 1,900 courses designed for Class 9 till post-graduation and is accessible to ‘anyone, anywhere at any time.’ In addition, the MoE is also running other learning platforms such as Diksha, e-pathasala, NIOS (National Institute of Open Schooling which are managed by the National Council of Education Research and Training (NCERT). In these endeavours, the new addition is launch of PM e-Vidya, a digital education initiative. The programme was launched in May 2020 as part of covid relief package under Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, several digital efforts are emerging and evolving quickly. The recommendations of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 further encourage the governments’ policy priorities for online education. The policy envisages technology as an integral part of education planning, management, administration, teaching, learning, assessment, teachers’ training, and professional development. One of its recommendations is to harness technology in education through app-based learning, online student communities, and lesson delivery beyond ‘chalk and talk.’ While NEP 2020 acknowledges the need to bridge the digital divide and improve digital infrastructure, it does not explicitly mention how investments will be drawn to implement the policies on the ground.

Are we ready?

At present, e-Learning might seem a viable solution to fill the void made due to the lack of classroom learning. The pandemic also highlights the necessity to build robust online environments to provide stability in learning. However, there are a number of challenges in the adoption of technology in education.

Poor digital infrastructure is the key challenge in India for scaling up active use of technology in education. Only 8% of Indian households with young members have both a computer and an internet connection. Even if there is access, given the cost associated with Edtech products, it is difficult for lower and lower-middle income households to bear the financial burden. Unfortunately, there is no substantial budgetary allocation from government on strengthening the digital base.

On the supply side, not enough evidences are available about the outcomes claimed by Edtech start-ups. The performance of Edtech companies is evaluated largely from market research and the number of customers, rather than any validation of educational outcomes. Secondly, the online education being imparted by the ed-tech firms miss a quality check. The contents offered by many of them are either not pedagogically sound or not context specific. Lack of affordable vernacular content also limits users.

Without creating a conducive learning ecosystem, the drive for Edtech seems to be favourable for a certain section of students having access, affordability and flexibility in choosing options. The increased policy attention towards active use of technology in education, and at the same time lacklustre policy response towards existing digital divide might shift the target of ‘universal access to education’ further.

30 September, 2021

30 September, 2021