An important comparative point in relation to the Union Budget for 2024-25 is with regard to the evaluation as to how effectively it builds on the interim budget’s preliminary projections on ‘Viksit Bharat’ by 2047. The interim budget, presented in February 2024, was widely perceived to have set the stage for a vision of a ‘Viksit Bharat’ by 2047, emphasising inclusive and comprehensive development. With the final budget now in place, it is essential to examine how the government has advanced its agenda and addressed key areas of concern.

It is well known that when narratives of development are built solely around economic growth and technological advancements, there is a potential for essential human needs to get blurred into the background. A key parameter in terms of essential human needs is WASH, an development related acronym for sectors such as Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. Over the past few decades, WASH is at the core of development discourse across the world.

Looking at the current Union budget, the Ministry of Jal Shakti, that is mandated to steer India towards universal access to drinking water and sanitation, has indeed received increased budgetary allocations, notably for the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), while the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) received a similar allocation as last year. Overall, the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitations budget rose to Rs 77,390.67 crores in 2024-25 (BE) from Rs 77,032.64 crores in 2023-24 (RE- Revised Estimate ). However, the proportion of GDP to this sector has slightly gone lower to 0.23 percent from the 0.26 percent in 2023-24 (RE).

Need to Enhance Institutional Capacities at State and Local Levels

At first glance, the consistent budget increase for JJM and the unwavering funding for SBM seems to testify the government’s dedication to this sector. Yet, the intricacies reveal a focus on WASH infrastructure over essential human resources and institutional measures. One needs to also see the gaps between budget estimates, revised estimates, and actual expenditures.

The 2022-23 parliamentary standing committee on water resources reported significant underutilisation of funds allocated to JJM, indicating a gap between budgetary intentions and actual progress. As water and sanitation are listed as State subjects, such differences in expenditure underscore systemic and institutional inefficiencies in terms of state-level planning and implementation. Evidently, this emphasises the need for more strategic allocations by the centre, in order to address institutional challenges at State and sub-State levels.

Need Focus on Sustainability of Water Supply and Infrastructure

In specific terms, the JJM witnessed a budgetary increase, allocating Rs 70,163 crores in 2024-25 (Budget Estimate -BE), from the revised estimate of Rs 70,000 crores in 2023-24. While this seems to indicate a robust commitment for ensuring tap water connections across rural India, the sustainability of water sources also needs to be examined and emphasised. The allocation for the Atal Bhujal Yojana aimed at groundwater management, under the Department of Water Resources, stands at Rs 1,778 crores for 2024-25 (BE). Clearly, this requires enhanced focus and investment commensurate with the new focus to ensure the programme’s expansion beyond the seven States where it is currently being implemented. Experts have systematically warned that ground water availability will become a burning issue in all States, sooner or later.

Being the fourth year of JJM, it is vital to bring up water conservation, community engagement, and sustainable water management practices into priority, beyond infrastructure development. This also necessitates widespread behavioural change, capacity-building, data generation for water planning, water metering for usage analysis, pricing strategies for usage control, and enhanced hygiene practices. Additionally, it is crucial to examine how allocations ensure sustainable operations, management, and maintenance of existing infrastructure.

Need for Prioritising Quality in Coverage of Water Supply

Achievements under JJM, such as the increase in water connections to nearly 13.97 crore households, signal initial progress towards ‘Har Ghar Jal’, the programme designed to ensure water for every home as well as Functional Household Tap Connections (FHTC). The very concept of ‘Har Ghar Jal’ self-professedly encompasses quantity, quality, and access, in contrast to simple connections for tap water. Quality of water supplied is paramount in this framework.

While some basic measures at the community level have been initiated in this direction, the availability of accredited water quality labs with adequate human and other resources in all districts is bound to be a significant future concern. In this regard, it is important to recognise that the reasonably higher progress reported at the national level is the cumulative of the total coverage of a few States, while there are several States still showing suboptimal progress. This uneven access to clean water is a reminder of the complexities involved in achieving universal FHTCs.

Need to Address Pending Last Mile Challenges under SBM

The second phase of SBM, despite its aims to obtain and sustain the Open Defecation Free (ODF) and comprehensive waste management status, has not seen proportional budget increases, especially in comparison to JJM. The 2024-25 budget allocation for SBM (Rural) remains at Rs 7,192 crores, unchanged from the previous year’s Revised Estimates, at a time when substantial investments are crucial for achieving its ambitious goals. The budget for the SBM 2.0 initiative needs enhancement, especially for critical areas like grey-water management, solid-waste management, and faecal sludge management.

Apart from this, there is also the need to address gaps in toilet coverage and accessibility, all with a focus on community involvement and behavioural change. Training of local government actors, local level human resources and cross-departmental collaboration have also gone thin after the huge campaign and mobilisation during the SBM’s first phase. The reliance on deployment of Central Finance Commission funds to Panchayats to address budgetary gaps poses new challenges, particularly due to limited capacity of rural bodies. Over and above this, there are also issues concerning State level departmental coordination. Central to this coordination question is the fact that the controlling departments for local bodies and the SBM line departments are different. Challenges related to using finance commission funds for SBM priorities intensify in States with scheduled areas, wherein the scheduled area councils are not bound by SBM guidelines.

Need Increased Allocations for Urban WASH

While it can be seen that rural WASH is better supported, urban areas, particularly urban informal settlements, require more attention in budgeting processes and allocations. The current schematic focus and budgets under Urban SBM, Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), and similar programmes require a significant increase, following an inclusive WASH framework for the urban informal settlements. The model that was set up by Odisha in this regard could be seen as a reference. To realise safe sanitation in towns, it is critical to cover the urban informal settlements well, wherein the current allocation for Individual Household Latrine (IHHL) is insufficient. It is also imperative to suggest and promote sanitation technologies that could be implemented within the available minimum spaces in urban areas. The relatively higher cost implications here should be seen as inevitable for urban development. Waste management is another underfunded area which needs attention.

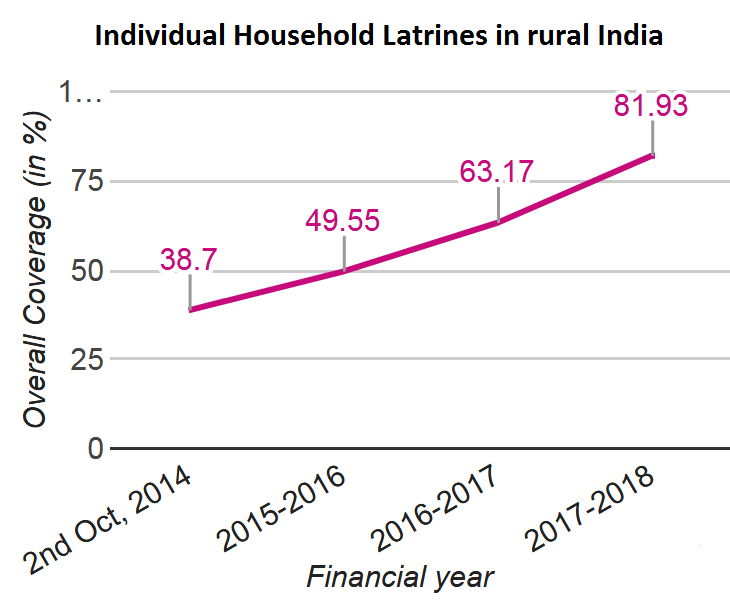

Individual Household Latrines has been increasing at a steady rate since 2018. Source: Wikipedia

In 2023-24, SBM’s urban budget increased to Rs 5,000 crore(BE) from previous year’s actual spending of Rs 1,926 crore, but was later adjusted down by 49 per cent to Rs 2,550 crore (RE) a level maintained in the 2024-25 (BE) budget. The AMRUT scheme, with a component aiming at improving essential infrastructure for underprivileged populations, received only 10 percent of the total budget for the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, repeating last year’s allocation pattern. However, funding for AMRUT increased by 53 per cent to Rs 8,000 crore from previous year’s revised estimate, aiming to extend water supply to around 4,800 statutory towns as one of its objectives.

Despite all this, the allocations still fall short the its ambitious targets for tap water and sewer connections, underscoring the necessity for enhanced investment to accommodate rising rural-to-urban migration and to meet the needs of urban poor. There is a USD 200 million Asian Development Bank loan granted for SBM (U) 2.0 during 2023, targeting garbage-free cities. However, positive reflections of this are yet to be seen in the budget.

Need to Integrate Crucial Hygiene and Health Linkages

Cultural barriers pose additional impediments to WASH systems, particularly around hand hygiene and menstrual hygiene, which hamper efforts to change sanitation behaviours and garner societal acceptance. The recent draft national policy on Menstrual Hygiene addresses one part of this. However, the project will not succeed without adequate funding and a strong implementation framework. Hand hygiene is another critical area, which continues to remain a challenge, despite the lessons from the Covid pandemic. The challenges on these issues mount further, when and where delivery of consistent water supply and sanitation services face obstacles, notably in remote areas and urban informal settings.

A focused hygiene agenda, supported by water supply, expanded educational outreach, and community involvement, is essential for achieving hygiene objectives and establishing their health linkages. Hygiene is an area that requires a clear roadmap, departmental ownership, and fiscal focus, which needs to be prioritised.

Need to Reimagine India’s WASH Priorities, after a decade of ‘Missions’

Addressing these critical gaps, the new government (or the Narendra Modi led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government 3.0) may aim to introduce an integrated WASH framework that aligns with the multisectoral SDG commitments with WASH linkages. This may require an architectural overhaul, both in urban and rural settings, featuring targeted and comprehensive allocations to guarantee the sustainability of investments.

With the first budget of the current government now in place, it is clear that while some advancements have been made, there is an urgent need for bold, forward-looking measures to guide India towards a more grounded, equitable, and sustainable WASH future.

1 August 2024

1 August 2024